Overview

This part of the guide covers our best practices for more advanced testing techniques, which are done at the end of the development cycle only (as they're more time and caffeine-consuming) and test the system as a whole.

We add more advanced testing techniques with one or both of the following approaches:

Having these extra-steps consolidates the testing framework built around our protocol: unit tests are studying how a given part is working, integration is ensuring how multiple parts are working together during defined cases, property-based fuzzing will now study how the whole protocol is working in a big number of cases with multiple interactions (stateful) and formal verification will study how the protocol is working in every possible case (usually statelessly). In practice, most of our invariants are tested via fuzzing.

Properties & Invariants

During the design phase of a new project, we start collecting the protocol properties and invariants (either from the new design or pre-existing specification/requirements). At this stage of the development, this means having a bullet point list describing what and how the project will behave. It includes invariants, characteristics which are always true, or some more specific scenarios, called properties (the distinction being pedantic only, both terms are used interchangeably).

In short, think of how the protocol would be described as a whole, from a helicopter point of view. With the list of properties, someone should be able to create a system which will behave in the same way as the one tested, without knowing the implementation details.

For a more detailed approach on our way of finding and writing invariants, check the Invariants writing strategy.

These properties are the foundations of the last step in the tests implementation, as they are the invariants which will be challenged via formal verification or fuzzing campaign. It is therefore important to make sure they're well written from the start, with no stones left unturned.

📝 Exercise: try to find the properties/invariants of this system

uint256 totalMinted;

mapping(address owner => uint256 balance) balanceOf;

function mint(uint256 amount) external {

balanceOf[msg.sender] += amount;

totalMinted += amount;

}

function burn(uint256 amount) external {

if(balanceOf[msg.sender] < amount) revert("minBal");

balanceOf[msg.sender] -= amount;

}

✅ Solution

- totalMinted is the sum of all the mint

- an address cannot burn more than its current balance

- an address balance is the sum of all its mints, minus its burns

- totalMinted never decreases

Special cases: for math library or functions, properties can take the form of the underlying mathematical properties describing the operation (eg an addition is commutative, has a neutral element 0 over the real numbers, etc), as well as hedge cases (0, max, etc).

📝 Exercise: try to find the properties/invariants of this system

function mul(uint256 a, uint256 b) external returns(uint256) {

unchecked {

if( a*b / a != b) revert("OF");

}

return a * b;

}

✅ Solution

- Unit: mul should be associative, so that

mul(mul(a, b), c)is the same asmul(a, mul(b, c)) - Unit: mul should be commutative

- Unit: mul should be distributive

- Unit: mul should have 1 as identity element

- Unit: mul should have 0 as absorbing element (this is both a property and a hedge case)

- Unit: should throw if a*b is greater than uint256 max

General tricks

Many approaches to conduct a testing campaign can be taken and are “correct”, yet having a systematic and well-organized one helps a lot. Here are some take-aways from previous project, which might help:

- Start by reviewing the properties and invariants. See the doc above on how to find them, keeping in mind that "having only a few selected critical (and well tested) invariants is better than a list of 50 highly complex, poorly defined or understandable, ones".

- Setup for fuzzing or formal verification can be taken from the integration tests - rather as a template than blindly pasting them, as to avoid inheriting any complexity debt coming from setting up a fork for instance.

- We tend to start from one given path (ie "how to test the first invariant" for instance), including handlers to cover it, then incrementally add handlers to cover other paths (instead of, for instance, adding handlers for every functions and deal with the complexity later).

- Test functions are easier to grasp when expressed in Hoare logic (precondition, including pranks; action, as a single call; postcondition). In the rare case where multiple actions are conducted within a single test function, this is expressed as multiple Hoare logic blocks.

function testOne() public {

// Pre-condition

vm.warp(123);

address caller = address(123);

deal(caller, 1 ether);

vm.prank(caller);

// Action

target.deposit{value: 1 ether}();

// Post-condition

assert(target.balance(caller), 1 ether);

}

-

Assessing a test function has 3 steps, once the test passes:

-

Check the coverage to see if the test itself is not (silently) reverting and if the target code is actually covered

-

Make sure both sides of a revert are covered with try - assert - catch - assert.

-

Mutate the property itself or the target code. See Mutation testing for more details

-

-

Any state which can be accessed or reconstructed from the target should be accessed this way (even if some needs to be recomputed, for instance reducing individual balances to a cumulative sum). If there is no way to do so, then a ghost variable should be used (either in the relevant handler, or, usually easier, in a “BaseHandler” contract, with relevant helper functions).

-

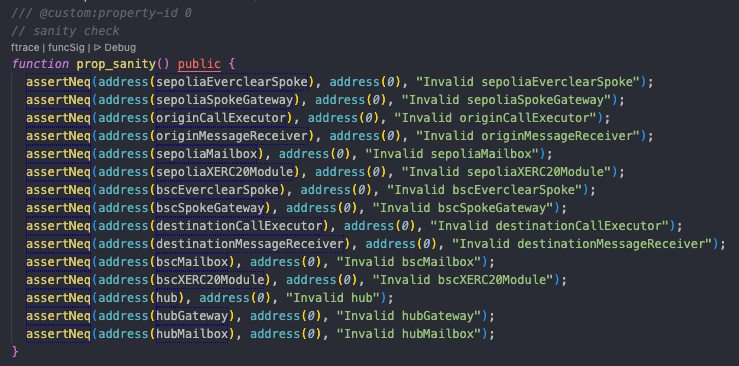

Always start with validating the initial setup and sanity checks as “property-0”. For instance, address of the deployed contract ≠ 0, calling some constant variables, etc.

-

Function names:

setUp()this is the same function as for regular tests, and is executed before each invariant runinvariant_*this is the function which contains the invariant to test _handler_*this is where we implement handlers around contract calls

Reporting found issues

Sometimes when testing, you will find bugs and hopefully they won’t be Forge and Kontrol bugs but actual errors in the project’s code. The first step in handling the issue should always be notifying the dev team and validating the finding. Then depending on the validity and fixability of the issue we have multiple choices.

Invalid finding

If the finding could not be confirmed by the dev team, we should look for errors in the test and fix them.

Valid finding

If the finding is confirmed, the first step is always gathering the details and filling in the report under the project’s internal testing page. During the process, you will assign the finding a unique ID and severity.

If the issue can be fixed, we should convert the Forge / Kontrol test into a simple unit or integration test, and specify the issue ID in the test’s natspec.

If the issue won’t be fixed, we still need a way to reproduce it. To simplify this process, we have settled on the following steps:

- If it doesn’t exist yet, create a

PropertiesFailingcontract and inherit it inInvariant - In the failing properties contract, add a test for the found issue. Make sure to specify the issue ID in the natspec.

- In the test setup, exclude this contract using

excludeContract(address(propertiesFailing))